5th May Sunday Brings La Palabra to Avenue 50 Studio

Michael Sedano

La Palabra hosted by Karineh Mahdessian ordinarily brightens the fourth--the final--Sunday of every month, but because May 2015's calendar quirk brought a fifth Sunday, La Palabra bided its time until the fifth, final, Sunday.

Dynamic hostess Karineh Mahdessian confessed to butterflies fifteen minutes before the two o'clock curtain. She looked across the empty main gallery of Highland Park's Avenue 50 Studio and saw an empty circle of chairs.

As La Palabra has proven year after year, month after month, people thronged through the front and side doors and by 2:00, Mahdessian was smiling broadly at the full house. Mejor, as the reading progressed, the house added visitors until La Palabra became an SRO event.

Featured Poets: Jenuine Poetess and Thelma Reyna

Tempus fugit! One of the featured readers, Jenuine Poetess, was on her way to LAX to board a flight to Italy. The ticketed passenger motivated the on-the-dot start.

Jenuine Poetess wrapped her reading and headed out the door toward her 100 Thousand Poets for Change event in Salerno. The next global 100TPC event comes in September. More information, and sign-ups here.

The second featured poet, Thelma Reyna followed the as-always fully subscribed Open Mic.

Reyna, Poet Laureate of Altadena, recently launched her ALTADENA POETRY REVIEW: ANTHOLOGY 2015. Reviewer Carol Davala observes, "This well-rounded book showcases work representing a broad spectrum of poetic style and subject matter, and it includes details indicative of spanning generations, cultural diversity, and a special blend of topical life experiences. From traditional formats to free-flowing verse, rhyming acrostics, elemental haiku and tankas, the poetic voices illuminate childhood memories, observe modern technology, and reflect on nature for both its beauty and consequences."Here's a link to the full review.

Thelma Reyna knows how to hold an audience. Today's reading threaded her work with a running commentary focused on a poet's sources of inspiration. She transitioned between readings telling biographical stories, current events items, and other material that lent her compositional urgency.

Among the places a poet finds poems is familia. James Reyna, Thelma's husband, beamed throughout the reading, knowing first-hand the sweat and tears that produced the works that Thelma reads so effectively, as if the poems were writing themselves in the moment.

Sixth Month's First On-line Floricanto

Francisco X. Alarcón, Carl Allen Begay, José Hector Cadena, Ángel Mario Escobar, Sam Hamod, Briana Muñoz, Sharon Elliott

With Father's Day an upcoming June ritual, today La Bloga-Tuesday happily celebrates the first of two On-line Floricantos. The Moderators of Poetry of Resistance: Poets Responding to SB 1070, led by peripatetic poet Iris de Anda, nominate seven poems to launch the pair of June On-line Floricantos.

POETA MACEHUAL*

por Francisco X. Alarcón

soy un poeta

macehual, seguidor

de mariposas

un trovador

sin corte, sin cuartel

que anda a pie

por los senderos

sin caminantes fuera

de los linderos

mi voz es flor,

canto silvestre libre

como el rocío

la Luna de abril

es mi madre del cielo

que me bendice

el río revuelto

que un huracán desata

es hermano mío

soy un poeta

hacedor de versos

de vida y lluvia

sin otro templo

que la cima del monte

bajo el Sol

mi cara la hallo

en las caras y sonrisas

de mi gente

soy un poeta

macehual, seguidor

de mariposas

sin otro techo

que el cielo raso

lleno de estrellas

mi bandera es

blanca nube del cielo,

paloma de paz

el mundo entero

-ya sin fronteras- es

mi casa y solar

MACEHUAL (COMMON FOLK) POET

by Francisco X. Alarcón

I am a macehual

poet, a follower

of butterflies

a troubadour

with no court or quarter,

a hiker on foot

trekking paths with

no other walkers, beyond

well travelled ways

my voice is a flower,

a wild song free

like the dew

April’s Moon is

my mother blessing me

from the sky

the unruly river

a hurricane brings about

is my own brother

I am a poet,

a wordsmith of verses

for life and rain

with no other temple

than the mountain summit

under the Sun

I find my face

on the faces and smiles

of my people

I am a macehual

poet, a follower

of butterflies

with no other ceiling

than the open sky

full of stars

my sole flag is

a white cloud in the sky,

a dove of peace

the whole world

-already borderless- is

my home and backyard

FOWK POET

Francisco X. Alarcón

am a fowk makar,

a follaer

o butteries

a fowk singer

wi nae coort or quarter,

a traiker on fuit

traikin peths alane,

ayont

weill-traikit weys

ma vice's a flooer,

a wull sang lowse

lik the deow

Aprile's muin's

ma mither sainin me

frae the lift

the gurly watter

blowster steert

is ma ain brither

am a makar,

wrochtin verses

fir life an weet

wi nae ither tempel

than yon muntain peen

unner the sin

a fin ma neb

in aw the smiles

o ma ain fowk

am a fowk makar,

follaer

o butteries

wi nae ither ruif

nor the apen lift

fou o sterns

ma yin flag's

a fite clud i the lift,

a doo o Pace

the hail warl

-a'ready mairchless -

is ma hame, ma back coort

Cruzando

Por José Hector Cadena

¿Qué estrategias existen para calmar las ansias que surgen

cuando el border agent me cierra la reja?

Me hubiera comprado una nieve de limón pero

es demasiado tarde para buscar un alivio frío azucarado

no hay remedio más que esperar en mi carro encajonado

entre cámaras y letreros y perros enloquecidos por encontrar droga,

todo esto es un juego para ellos, un juego

Con la música de la radio me tranquilizo y me doy cuenta

que tal vez deba practicar la paciencia,

pronto regresará el borde agent de llevar a otro sospechoso

al secondary inspection a que le pregunten de todo y de más

Al abrirse la reja, el border agent me señala que me arrime

y pregunta de donde vengo, porque fui, que traigo, en un tono

que intenta hacerme sentir desposeído, pero al ver que no

me tiembla la voz, sigue a inspeccionar mi carro, revolviendo y

azotando con un tubo de metal, tap, tap, tap,

Meet The Poets

Francisco X. Alarcón, José Hector Cadena, Ángel Mario Escobar, Sam Hamod, Briana Muñoz, Sharon Elliott

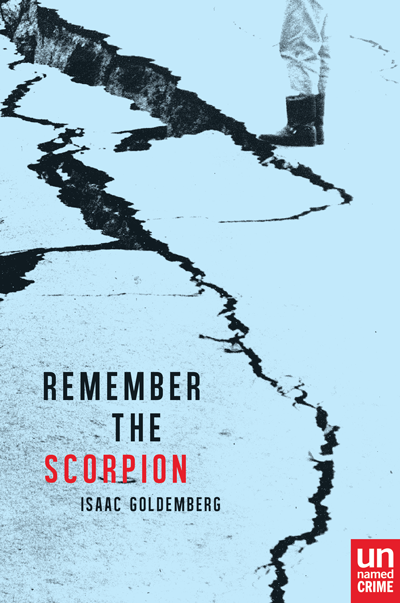

Francisco X. Alarcón, award-winning Chicano poet and educator, was born in Los Angeles, grew up in Guadalajara, Mexico, and now lives in Davis, where he teaches at the University of California. He is the author of thirteen volumes of poetry, including his most recent books, Canto hondo / Deep Song (University of Arizona Press 2015) and Borderless Butterflies / Mariposas sin fronteras (Poetic Matrix Press 2014). He is also the author of six acclaimed books of bilingual poems for children on the seasons of the year originally published by Children’s Book Press, now an imprint of Lee & Low Books. He is the founder the Writers of the New Sun community in Sacramento and also the creator of the Facebook page “Poets Responding to SB 1070.”

Jose Hector Cadena is a writer, poet, and collage artist. He grew up along the San Ysidro/Tijuana border. VONA fellow 2014, Jose’s work can be found in Cipactli, Transfer Magazine, Pacific Review, and more. He currently teaches at San Diego State University and Southwestern College.

Mario A. Escobar (January 19, 1978-) is a US-Salvadoran writer and poet born in 1978. Although he considers himself first and foremost a poet, he is known as the founder and editor of Izote Press. Escobar is a faculty member in the Department of Foreign Languages at LA Mission College. Some of Escobar’s works include Al correr de la horas (Editorial Patria Perdida, 1999) Gritos Interiores (Cuzcatlan Press, 2005), La Nueva Tendencia (Cuzcatlan Press, 2005), Paciente 1980 (Orbis Press, 2012). His bilingual poetry appears in Theatre Under My Skin: Contemporary Salvadoran Poetry by Kalina Press.

Sam Hamod is an internationally awarded poet, nominated for the Nobel Prize by Carlos Fuentes and for the Pulitzer Prize by Ishmael Reed and Ray Carver; he has published15 books of poems and runs the websites, www.contemporaryworldpoetry.com

and www.contemporaryworldliterature.com He has a Ph.D from the Writers Workshop and has taught at the Univ of Iowa and at other leading universities in America and overseas. He may be reached for readings, books and lectures at: drsamhamod@gmail.com

Briana Muñoz is a writer from San Marcos, California. She is a full time student and enjoys writing about what she observes around her on her free time. She writes fictional short stories, creative non-fiction and poetry. Briana is striving to publish her works some time in the near future.

Born and raised in Seattle, Sharon Elliott has written since childhood. Four years in the Peace Corps in Nicaragua and Ecuador laid the foundation for her activism. As an initiated Lukumi priest, she has learned about her ancestral Scottish history, reinforcing her belief that borders are created by men, enforcing them is simply wrong.

She has featured in poetry readings in the San Francisco Bay area: Poetry Express, Berkeley, CA in 2012 and La Palabra Musical, Berkeley, CA in 2013.

She was awarded the Best Poem of 2012, The Day of Little Comfort, Sharon Elliott, La Bloga Online Floricanto Best Poems of 2012, 11/2013, http://labloga.blogspot.com/2013/01/best-poems-of-2012.html

On-line Poetry Anthology: Chicanas en Italia

In her column Monday, Xánath Caraza announced the publication in Italy of seven Chicana poets. Here's a YouTube that includes readings of the works, in Spanish and translated into Italian.

The cover arte is by noted Chicana artist Pola Lopez. Pola's Los Angeles studio shares space in Avenue 50 Studio.

Submissions

Razorhouse Magazine

Now There Is One

Once there were two Raza-Centric Writers Conferences. With the suspension--or demise--of the National Latina Latino Writers Conference formerly hosted by the National Hispanic Cultural Center in Albuquerque NM, only the East Coast iteration remains, the Comadres and Compadres Latino Writers Conference in New York City.

Offering workshops, camaraderie, keynote addresses, comida, and, most importantly, individual interviews with influential gente in the publishing industry, the 4th annual conference helps open the door that quality work keeps open.

Click here for registration datos.

Michael Sedano

La Palabra hosted by Karineh Mahdessian ordinarily brightens the fourth--the final--Sunday of every month, but because May 2015's calendar quirk brought a fifth Sunday, La Palabra bided its time until the fifth, final, Sunday.

Dynamic hostess Karineh Mahdessian confessed to butterflies fifteen minutes before the two o'clock curtain. She looked across the empty main gallery of Highland Park's Avenue 50 Studio and saw an empty circle of chairs.

As La Palabra has proven year after year, month after month, people thronged through the front and side doors and by 2:00, Mahdessian was smiling broadly at the full house. Mejor, as the reading progressed, the house added visitors until La Palabra became an SRO event.

Featured Poets: Jenuine Poetess and Thelma Reyna

Tempus fugit! One of the featured readers, Jenuine Poetess, was on her way to LAX to board a flight to Italy. The ticketed passenger motivated the on-the-dot start.

Jenuine Poetess wrapped her reading and headed out the door toward her 100 Thousand Poets for Change event in Salerno. The next global 100TPC event comes in September. More information, and sign-ups here.

The second featured poet, Thelma Reyna followed the as-always fully subscribed Open Mic.

Reyna, Poet Laureate of Altadena, recently launched her ALTADENA POETRY REVIEW: ANTHOLOGY 2015. Reviewer Carol Davala observes, "This well-rounded book showcases work representing a broad spectrum of poetic style and subject matter, and it includes details indicative of spanning generations, cultural diversity, and a special blend of topical life experiences. From traditional formats to free-flowing verse, rhyming acrostics, elemental haiku and tankas, the poetic voices illuminate childhood memories, observe modern technology, and reflect on nature for both its beauty and consequences."Here's a link to the full review.

Thelma Reyna knows how to hold an audience. Today's reading threaded her work with a running commentary focused on a poet's sources of inspiration. She transitioned between readings telling biographical stories, current events items, and other material that lent her compositional urgency.

Among the places a poet finds poems is familia. James Reyna, Thelma's husband, beamed throughout the reading, knowing first-hand the sweat and tears that produced the works that Thelma reads so effectively, as if the poems were writing themselves in the moment.

Open Mic Frequent Guests and a Debut

Poetry at Avenue 50 Studio is a regular event, with La Palabra and the Bluebird series. The Open Mic sign-up fills quickly with local poets as well as visitors to the region making their first time presenting in Highland Park.

Given the relaxed atmosphere, many sign with only their first name. Some poets arrive while the reading is in progress, or do not sign up yet elect to join the readers on-the-fly.

Karineh Mahdessian watches the time carefully but generously finds space for readers not on the list. "Anyone want to read?" The hapless photographer is left high and dry by that, able to create an image but unable to ID some readers.

Ni modo; among the frustrations of a poetry foto essay is being unable to share the poems themselves, so what's one additional frustration? Lacking the poet's name, or last name, simply adds to the reasons to attend the next poetry event at Avenue 50.

|

| Left to right, top-bottom: Don Kingfisher Campbell. idi. Jackie. Art. Mahdessian insisted Art return with his gut-strung guitar to play a bit of Bach. |

|

| A fabulous reading about the poet's notches on a bed post entertained. Mira Mataric. Poet in a black shirt works from memory. Briony James. |

|

| Among the pleasures of an Open Mic, a debut! Marsha Oseas shares her first public reading. |

|

| Seven, Brian Dunlap, energetic G T Foster uses the full area; an unidentified gentleman. |

|

| Prof Jonathan Vos Post, like Foster, used the space available to maximum advantage. His Space Shuttle necktie mirrors his subject, the ghost in the machine. |

|

| Victor, Vos Post, Pauline Wiland, C E Jordan |

|

| C E Jordan invites gente to an upcoming poetry event |

Photography note: ISO3200, plus 2 stops against the bright windows produces acceptable images, most 1/50 f/5.6. The seating circle creates challenges for photographer and poets. Reading from one's seat severely limits the effectiveness of text-bound readers. The photographer leans and twists to capture near-by readers. All-in-all, such a setting is fun.

Fabulous Mural Event Features Stellar Artists

La Bloga friend, Isabel Rojas-Williams, Executive Director of Mural Conservancy of Los Angeles (MCLA) sends the following:

It would be wonderful should you be available to join us at Couturier Gallery for "L.A. Muralists: In Their Studios ll," an exhibition showcasing pioneer muralists, mid-career, and emerging artists, thereby giving a new generation of artists the opportunity to connect with some of LA’s most prominent public artists.

10% of the proceeds will benefit The Mural Conservancy of Los Angeles. Looking forward to seeing you there & thank you for your support!

What: L.A. Muralists: In Their Studios ll

When: June 6th, 6-8pm (opening reception)

Where: Couturier Gallery, 166 N. La Brea Ave, LA 90036

Who: Angelina Christina, David Botello, Pablo Cristi, Wayne Healy, Judithe Hernández, Alex "Defer" Kizu, Kofie, Lydia Emily, Kent Twitchell, John Valadez, and Richard Wyatt

Francisco X. Alarcón, Carl Allen Begay, José Hector Cadena, Ángel Mario Escobar, Sam Hamod, Briana Muñoz, Sharon Elliott

With Father's Day an upcoming June ritual, today La Bloga-Tuesday happily celebrates the first of two On-line Floricantos. The Moderators of Poetry of Resistance: Poets Responding to SB 1070, led by peripatetic poet Iris de Anda, nominate seven poems to launch the pair of June On-line Floricantos.

POETA MACEHUAL*

por Francisco X. Alarcón

soy un poeta

macehual, seguidor

de mariposas

un trovador

sin corte, sin cuartel

que anda a pie

por los senderos

sin caminantes fuera

de los linderos

mi voz es flor,

canto silvestre libre

como el rocío

la Luna de abril

es mi madre del cielo

que me bendice

el río revuelto

que un huracán desata

es hermano mío

soy un poeta

hacedor de versos

de vida y lluvia

sin otro templo

que la cima del monte

bajo el Sol

mi cara la hallo

en las caras y sonrisas

de mi gente

soy un poeta

macehual, seguidor

de mariposas

sin otro techo

que el cielo raso

lleno de estrellas

mi bandera es

blanca nube del cielo,

paloma de paz

el mundo entero

-ya sin fronteras- es

mi casa y solar

* Macehual: término náhuatl (azteca) para la gente común que forma la mayoría del pueblo y cuya labor constituye el meollo vital de la sociedad.

MACEHUAL (COMMON FOLK) POET

by Francisco X. Alarcón

I am a macehual

poet, a follower

of butterflies

a troubadour

with no court or quarter,

a hiker on foot

trekking paths with

no other walkers, beyond

well travelled ways

my voice is a flower,

a wild song free

like the dew

April’s Moon is

my mother blessing me

from the sky

the unruly river

a hurricane brings about

is my own brother

I am a poet,

a wordsmith of verses

for life and rain

with no other temple

than the mountain summit

under the Sun

I find my face

on the faces and smiles

of my people

I am a macehual

poet, a follower

of butterflies

with no other ceiling

than the open sky

full of stars

my sole flag is

a white cloud in the sky,

a dove of peace

the whole world

-already borderless- is

my home and backyard

Macehual: A Nahuatl (Aztec) term for the common folk, the bulk of the people, whose labor constitutes the vital core of society.

FOWK POET

Francisco X. Alarcón

am a fowk makar,

a follaer

o butteries

a fowk singer

wi nae coort or quarter,

a traiker on fuit

traikin peths alane,

ayont

weill-traikit weys

ma vice's a flooer,

a wull sang lowse

lik the deow

Aprile's muin's

ma mither sainin me

frae the lift

the gurly watter

blowster steert

is ma ain brither

am a makar,

wrochtin verses

fir life an weet

wi nae ither tempel

than yon muntain peen

unner the sin

a fin ma neb

in aw the smiles

o ma ain fowk

am a fowk makar,

follaer

o butteries

wi nae ither ruif

nor the apen lift

fou o sterns

ma yin flag's

a fite clud i the lift,

a doo o Pace

the hail warl

-a'ready mairchless -

is ma hame, ma back coort

Scots translation by John McDonald

Modern Day Warrior

By Carl Allen Begay - Navajo Nation - Nakai Dine/Tahnezahi Clans.

I am a modern day warrior

from the Navajo Nation

I am

living and surviving

the holocaust

on my people

the Indigenous People

of Turtle Island

aka America

We have survived

in spite of all

the tactics

by the u.s government

and all political corporate bullsh*t

of this country

We will not be wiped

off the face of this earth.

We are here

with loud voices

strong hearts

strong minds

strong bodies

strong spirits.

We are still here

and

We Shall Remain.

Cruzando

Por José Hector Cadena

¿Qué estrategias existen para calmar las ansias que surgen

cuando el border agent me cierra la reja?

Me hubiera comprado una nieve de limón pero

es demasiado tarde para buscar un alivio frío azucarado

no hay remedio más que esperar en mi carro encajonado

entre cámaras y letreros y perros enloquecidos por encontrar droga,

todo esto es un juego para ellos, un juego

Con la música de la radio me tranquilizo y me doy cuenta

que tal vez deba practicar la paciencia,

pronto regresará el borde agent de llevar a otro sospechoso

al secondary inspection a que le pregunten de todo y de más

Al abrirse la reja, el border agent me señala que me arrime

y pregunta de donde vengo, porque fui, que traigo, en un tono

que intenta hacerme sentir desposeído, pero al ver que no

me tiembla la voz, sigue a inspeccionar mi carro, revolviendo y

azotando con un tubo de metal, tap, tap, tap,

An Apology to My Children

By Ángel Mario Escobar

In the distant sleep

bodies I love

rest underneath

an old Amate tree

I smile

to ease

my broken

years

thirty-six

familiar

needles

knitting

histories

across borders

leaning on

secret tears

my children

know nothing of

Salvadoran rezos

prayers that won't give up

a long journey

echoing desperate footsteps

back in Morazan

a lineage crackling

like dry leaves

a child crying out for help

leaping red puddles

Now opening doors

so that tender kiss

can be passed on

to his children

who demand

to know

why daddy

mourns

while he

gazes

at the

deep

sea

What Shall We Say Today: What Shall We Do Today

By Sam Hamod

what now

can we say

about israelis...

who shoot young girls

or young soccer players

just for fun—

and what is worse,

they get away with it

not only that,

but

what can we say

about America

or

the americans who

support these atrocities,

whose government

gives money freely

to Israel,

while letting americans

go hungry,

go malnourished

lets cities go bankrupt

while their citizens still pay taxes

to this same government

that doesn’t care about them

what can we say

to a world

that allows this to go on

day

after day

after day

after day after day

while the world

looks the other way,

while the American president

preaches peace and justice, but

closes his eyes to these killings,

these brutalities,

who ignores it when Israelis

kill innocent American kids

who go to Palestine

to help

in humanitarian ways

what are we to say,

what are we to think,

what are we to feel,

are we to love Israel?

are we to love our

corrupt u.s. government?

are we to stand by

and let this evil continue?

shall we let ignorant alleged pastors,

lead ignorant people to love

this Israel that commits these crimes?

this is a day

we should all stand up,

this is a day

we should all write in protest

this is a day

we should all work and pray for justice

in a world gone mad,

in a world in the hands of devils,

especially those who run Israel and America

What Shall We Say Today: What Shall We Do Today

what now can we say about israelis... who shoot young girls or young soccer players just for fun—and what is worse, they get away with it

not only that, but what can we say about America or the americans who support these atrocities, whose government gives money freely to Israel, while letting americans go hungry, go malnourished lets cities go bankrupt while their citizens still pay taxes to this same government that doesn’t care about them

what can we say to a world that allows this to go on day after day after day after day after day

while the world looks the other way, while the American president preaches peace and justice, but closes his eyes to these killings, these brutalities, who ignores it when Israelis kill innocent American kids who go to Palestine to help in humanitarian ways

what are we to say, what are we to think,

what are we to feel,

are we to love Israel?

are we to love our corrupt u.s. government?

are we to stand by and let this evil continue?

shall we let ignorant alleged pastors, lead ignorant people to love this Israel that commits these crimes?

this is a day we should all stand up, this is a day we should all write in protest this is a day we should all work and pray for justice in a world gone mad, in a world in the hands of devils, especially those who run Israel and America

Raíz

By Briana Muñoz

You tell me that my scars are hideous.

I respond by saying “Hideous, tu madre.”

You formally inform me, in a Times New Roman letter

That my school work is “below average”

I ask you, “And exactly what is your definition of average?”

You laugh at the music blaring out of my

’93 nearly broken down pick-up truck

Rusty paint, chipping away like the old folks at the country club

But my music,

My music es de mi papá

This music represents beautiful colored women

In beautiful colored dresses

Multicolored ribbons

Floral head pieces

Canciones del país de mis abuelos

México Lindo

What my nana calls it.

So please, continue making fun

Of her thick Spanish accent

While you sit there

Ordering wet burritos and carne asada fries

From the Mexican food restaurant

Down the street from the multi-million dollar houses

In Del Mar

Because my culture is pinche beautiful

And so is my abuelita in her plaid mandil and sweaty forehead

And those mariachi lyrics I yell out proudly

Beautiful are my dark eyebrows which you make fun of

But I know they were passed down from my hard working mother

My culture is pinche beautiful; I refuse to allow you to tell me otherwise.

Violent Domesticity

by Sharon Elliott

what is it

they want

when they break a woman

wring her eyes dry

into a room

no bigger than a shotglass

carve her bones

into

a leftover casserole

sift her blood

into a bend

in the river

gag her

with her

own tongue

it must be

nothing

a momentary leap of groin

a game of tag

with eternity

theirs not hers

or maybe

the only something they can feel

is her suffering

through their

hands

her heart is broken

pumps only

at their whim

from its place underfoot

a power

so intoxicating

they refuse her escape

keep her breath

in a box

by the fireplace

like a match

to burnish

the night

when they break a woman

wring her eyes dry

into a room

no bigger than a shotglass

carve her bones

into

a leftover casserole

sift her blood

into a bend

in the river

gag her

with her

own tongue

it must be

nothing

a momentary leap of groin

a game of tag

with eternity

theirs not hers

or maybe

the only something they can feel

is her suffering

through their

hands

her heart is broken

pumps only

at their whim

from its place underfoot

a power

so intoxicating

they refuse her escape

keep her breath

in a box

by the fireplace

like a match

to burnish

the night

Copyright © 2015 Sharon Elliott. All Rights Reserved.

Francisco X. Alarcón, José Hector Cadena, Ángel Mario Escobar, Sam Hamod, Briana Muñoz, Sharon Elliott

Francisco X. Alarcón, award-winning Chicano poet and educator, was born in Los Angeles, grew up in Guadalajara, Mexico, and now lives in Davis, where he teaches at the University of California. He is the author of thirteen volumes of poetry, including his most recent books, Canto hondo / Deep Song (University of Arizona Press 2015) and Borderless Butterflies / Mariposas sin fronteras (Poetic Matrix Press 2014). He is also the author of six acclaimed books of bilingual poems for children on the seasons of the year originally published by Children’s Book Press, now an imprint of Lee & Low Books. He is the founder the Writers of the New Sun community in Sacramento and also the creator of the Facebook page “Poets Responding to SB 1070.”

Mario A. Escobar (January 19, 1978-) is a US-Salvadoran writer and poet born in 1978. Although he considers himself first and foremost a poet, he is known as the founder and editor of Izote Press. Escobar is a faculty member in the Department of Foreign Languages at LA Mission College. Some of Escobar’s works include Al correr de la horas (Editorial Patria Perdida, 1999) Gritos Interiores (Cuzcatlan Press, 2005), La Nueva Tendencia (Cuzcatlan Press, 2005), Paciente 1980 (Orbis Press, 2012). His bilingual poetry appears in Theatre Under My Skin: Contemporary Salvadoran Poetry by Kalina Press.

Sam Hamod is an internationally awarded poet, nominated for the Nobel Prize by Carlos Fuentes and for the Pulitzer Prize by Ishmael Reed and Ray Carver; he has published15 books of poems and runs the websites, www.contemporaryworldpoetry.com

and www.contemporaryworldliterature.com He has a Ph.D from the Writers Workshop and has taught at the Univ of Iowa and at other leading universities in America and overseas. He may be reached for readings, books and lectures at: drsamhamod@gmail.com

Briana Muñoz is a writer from San Marcos, California. She is a full time student and enjoys writing about what she observes around her on her free time. She writes fictional short stories, creative non-fiction and poetry. Briana is striving to publish her works some time in the near future.

Born and raised in Seattle, Sharon Elliott has written since childhood. Four years in the Peace Corps in Nicaragua and Ecuador laid the foundation for her activism. As an initiated Lukumi priest, she has learned about her ancestral Scottish history, reinforcing her belief that borders are created by men, enforcing them is simply wrong.

She has featured in poetry readings in the San Francisco Bay area: Poetry Express, Berkeley, CA in 2012 and La Palabra Musical, Berkeley, CA in 2013.

She was awarded the Best Poem of 2012, The Day of Little Comfort, Sharon Elliott, La Bloga Online Floricanto Best Poems of 2012, 11/2013, http://labloga.blogspot.com/2013/01/best-poems-of-2012.html

On-line Poetry Anthology: Chicanas en Italia

In her column Monday, Xánath Caraza announced the publication in Italy of seven Chicana poets. Here's a YouTube that includes readings of the works, in Spanish and translated into Italian.

The cover arte is by noted Chicana artist Pola Lopez. Pola's Los Angeles studio shares space in Avenue 50 Studio.

Submissions

Razorhouse Magazine

Now There Is One

Once there were two Raza-Centric Writers Conferences. With the suspension--or demise--of the National Latina Latino Writers Conference formerly hosted by the National Hispanic Cultural Center in Albuquerque NM, only the East Coast iteration remains, the Comadres and Compadres Latino Writers Conference in New York City.

Offering workshops, camaraderie, keynote addresses, comida, and, most importantly, individual interviews with influential gente in the publishing industry, the 4th annual conference helps open the door that quality work keeps open.

Click here for registration datos.